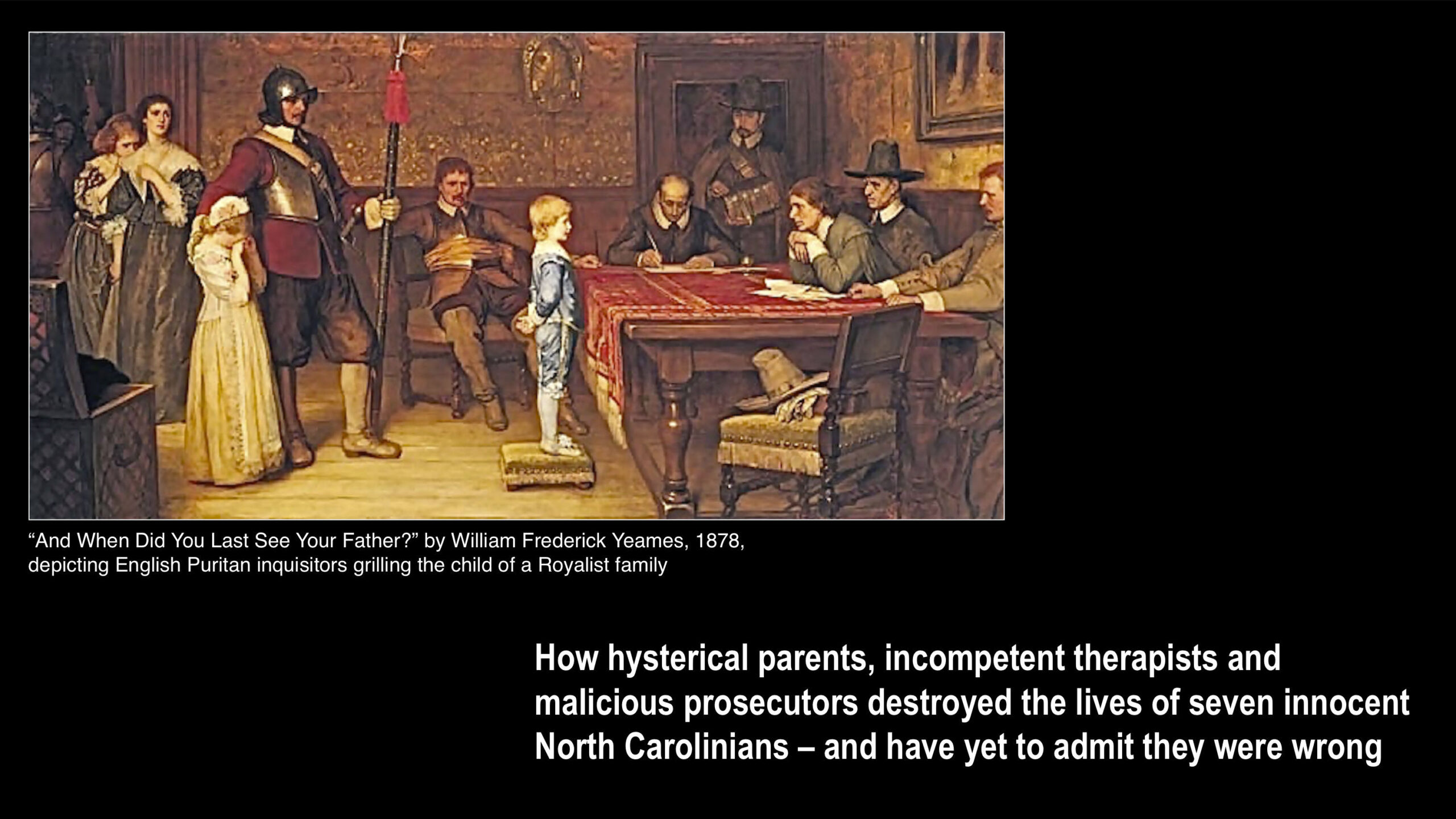

Rascals case in brief

In the beginning, in 1989, more than 90 children at the Little Rascals Day Care Center in Edenton, North Carolina, accused a total of 20 adults with 429 instances of sexual abuse over a three-year period. It may have all begun with one parent’s complaint about punishment given her child.

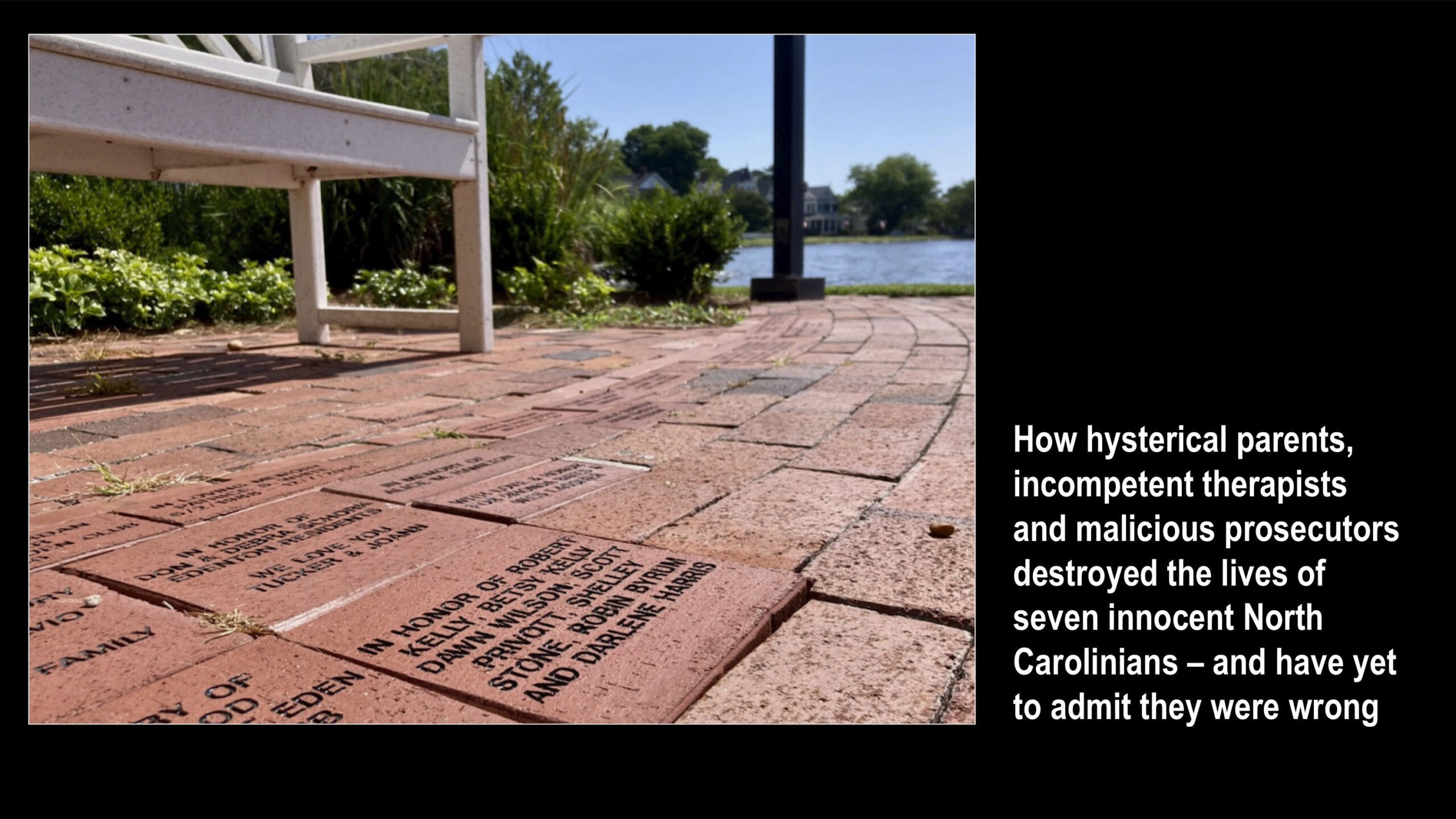

Among the alleged perpetrators: the sheriff and mayor. But prosecutors would charge only Robin Byrum, Darlene Harris, Elizabeth “Betsy” Kelly, Robert “Bob” Kelly, Willard Scott Privott, Shelley Stone and Dawn Wilson – the Edenton 7.

Along with sodomy and beatings, allegations included a baby killed with a handgun, a child being hung upside down from a tree and being set on fire and countless other fantastic incidents involving spaceships, hot air balloons, pirate ships and trained sharks.

By the time prosecutors dropped the last charges in 1997, Little Rascals had become North Carolina’s longest and most costly criminal trial. Prosecutors kept defendants jailed in hopes at least one would turn against their supposed co-conspirators. Remarkably, none did. Another shameful record: Five defendants had to wait longer to face their accusers in court than anyone else in North Carolina history.

Between 1991 and 1997, Ofra Bikel produced three extraordinary episodes on the Little Rascals case for the PBS series “Frontline.” Although “Innocence Lost” did not deter prosecutors, it exposed their tactics and fostered nationwide skepticism and dismay.

With each passing year, the absurdity of the Little Rascals charges has become more obvious. But no admission of error has ever come from prosecutors, police, interviewers or parents. This site is devoted to the issues raised by this case.

On Facebook

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

‘Understanding and Assessing’ ritual-abuse mythology

May 28, 2012

How would Bruce A. Robinson, founder of the comprehensive and widely respected ReligiousTolerance.org, describe the credibility now given ritual abuse?

“I am unaware of any child psychologist or similar specialist who still believes ritual abuse happened in child care facilities. I think there is a consensus that repeated direct questioning of young children will get them to reveal stories about events that never happened. Over time, these stories often become ‘memories.’ ”

Mr. Robinson, meet Kathleen Coulborn Faller, professor in the School of Social Work at the University of Michigan.

As previously noted, Dr. Faller in “Understanding and Assessing Child Sexual Maltreatment” (second edition, 2003) identifies herself as a true believer. Here’s how she makes her case:

■ “Responses to allegations of ritual abuse have undergone a transformation in the last 10 years, so that any case… elicits great skepticism. In fact, it is no longer au courant to believe in the existence of ritual abuse.”

Au courant? Does she really consider scientific research into children’s testimony to be some kind of fad, like pet rocks?

■ “The vigor of the attack against ritual abuse… reinforces the belief of some professionals, myself included, that there is substance to ritual abuse….”

What!? And where are these other professionals?

■ “Ultimately the backlash… resulted in the reversal of some criminal convictions involving ritual abuse (New Jersey v. Michaels, 1994; North Carolina v. Kelly, 1995)… ”

In fact, these convictions were overthrown not because public and professional opinion had begun to shift, but because their many legal defects were obvious to appeals courts.

● ● ●

I’ve again asked Dr. Faller to respond.

Prosecutors Book Club, please take note

April 19, 2014

“Is it possible to so modify child forensic interviewing that the sorts of errors described by Ceci and Bruck are minimized?…

“The primary problem is that most prosecutors and most so-called mental health professionals do not stay current….

“How likely, for instance, is it that a copy of ‘Jeopardy in the Courtroom’ will be found on your favorite prosecutor’s desk?”

– From “A Review of a Review of ‘Jeopardy in the Courtroom’ by Stephen J. Ceci and Maggie Bruck” at falseallegations.com

Moral panic drove men from day-care centers

Dec. 12, 2012

“In 1983, (the year of the first McMartin Preschool allegations), only 5 percent of day care providers were male. During the nine years of the moral panic, an alarming number of those male providers were accused of that new and horrific sex crime, satanic ritual abuse….

“Males left the profession in droves, seeking the comparative safety of male sex-role stereotyped employment. Day care was refeminized. Once again, primary responsibility for the care and socialization of young children was placed on the shoulders of low-paid women.”

– From “The Devil Goes to Day Care: McMartin and the Making of a Moral Panic” by Mary De Young in the Journal of American Culture (April 1, 1997)

How Bill Hart got better at playing dirty

Dec. 2, 2011

“Videotaped interviews made during the early cases (alleging day care ritual sex abuse) show that when children were allowed to speak freely, either they had nothing to say about abuse or they denied it ever happened to them.

“Videotaped interviews made during the early cases (alleging day care ritual sex abuse) show that when children were allowed to speak freely, either they had nothing to say about abuse or they denied it ever happened to them.

“Once it became obvious that these records would prevent guilty verdicts, prosecutors began advising investigators not to keep tapes or detailed notes of their work.”

– From “Satan’s Silence: Ritual Abuse and the Making of a Modern American Witch Hunt” by Debbie Nathan and Michael Snedeker (1995)

Perhaps the most significant difference in the two largest abuse trials was that McMartin defense attorneys were able to expose to jurors the prosecution therapists’ manipulative interview techniques, while Little Rascals attorneys were stymied by the premeditated unavailability of original documentation.

“After Bob Kelly’s indictment,” according to an article in the ABA Journal, “Bill Hart, a North Carolina deputy attorney general assigned to the case, traveled to Los Angeles to consult with McMartin prosecutors.

“He learned that McMartin jurors had criticized videotapes of therapist Kee McFarlane’s interviews with the children. She asked leading questions and rebuked children who did not tell of abuse….”

Hart could have brought back to North Carolina the lesson that interviewers shouldn’t “(ask) leading questions and (rebuke) children who did not tell of abuse.” Instead, he brought back the lesson that interviewers should leave no evidence of having used exactly those fraudulent techniques.

0 CommentsComment on Facebook